For now entrepreneurs are focussing their efforts on humanoid robots for warehouses and factories.

The highest profile of those is Elon Musk. His car company, Tesla, is developing a humanoid robot called Optimus. In January he said that “several thousand” will be built this year and he expects them to be doing “useful things” in Tesla factories.

Other carmakers are following a similar path. BMW recently introduced humanoid robots to a US factory. Meanwhile, South Korean car firm Hyundai has ordered tens of thousands of robots from Boston Dynamics, the robot firm it bought in 2021.

Thomas Andersson, founder of research firm STIQ, tracks 49 companies developing humanoid robots – those with two arms and legs. If you broaden the definition to robots with two arms, but propel themselves on wheels, then he looks at more than 100 firms.

Mr Andersson thinks that Chinese companies are likely to dominate the market.

“The supply chain and the entire ecosystem for robotics is huge in China, and it’s really easy to iterate developments and do R&D [research and development],” he says.

Unitree underlines that advantage – its G1 is cheap (for a robot) with an advertised price of $16,000 (£12,500).

Also, Mr Andersson points out, the investment favours Asian nations.

In a recent report STIQ notes that almost 60% of all funding for humanoid robots has been raised in Asia, with the US attracting most of the rest.

Chinese companies have the added benefit of support from the national and local government.

For example, in Shanghai there is a state-backed training facility for robots, where dozens of humanoid robots are learning to complete tasks.

So how can US and European robot makers compete with that?

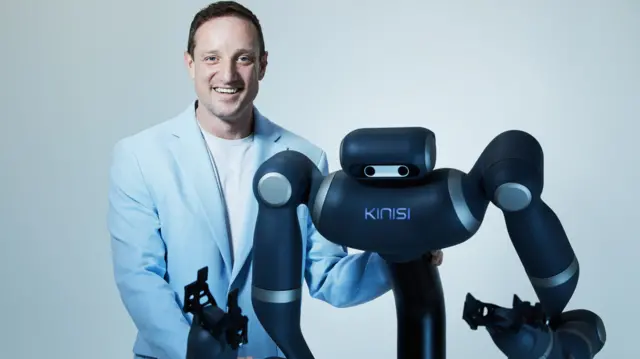

Bristol-based Bren Pierce has founded three robotics companies and the latest, Kinisi has just launched the KR1 robot.

While the robot has been designed and developed in the UK, it will be manufactured in Asia.

“The problem you get as a European or American company, you have to buy all these sub-components from China in the first place.

“So then it becomes stupid to buy your motors, buy your batteries, buy your resistors, shift them all halfway around the world to put together when you could just put them all together at the source, which is in Asia.”

As well as making his robots in Asia, Mr Pierce is keeping costs down by not going for the full humanoid form.

Designed for warehouses and factories, the KR1 does not have legs.

“All of these places have flat floors. Why would you want the added expense of a very complex form factor… when you could just put it on a mobile base?” he asks.

Where possible, his KR1 is built with mass-produced components – the wheels are the same as you would find on an electric scooter.

“My philosophy is buy as many things as you can off the shelf. So all our motors, batteries, computers, cameras, they’re all commercially available, mass produced parts,” he says.

Like his competitors at Unitree, Mr Pierce says that the real “secret sauce” is the software that allows the robot to work with humans.

“A lot of companies come out with very high-tech robots, but then you start needing a PhD in robotics to be able to actually install it and use it.

“What we’re trying to design is a very simple to use robot where your average warehouse or factory worker can actually learn how to use it in a couple of hours,” Mr Pierce says.

He says the KR1 can perform a task after being guided through it by a human 20 or 30 times.

The KR1 will be given to pilot customers to test this year.

So will robots ever break out of factories into the home? Even the optimistic Mr Pierce says it’s a long way off.

“My long term dream for the last 20 years has been building the everything robot. This is what I was doing my PhD work in I do think that is the end goal, but it’s a very complicated task,” says Mr Pierce.

“I still think eventually they will be there, but I think that’s at least 10 to 15 years away.”