Venus is not (geological) dead

A reevaluation of decades data suggests that strange circular formations on Venus could be “volcanic fire rings created by the ongoing geological activity

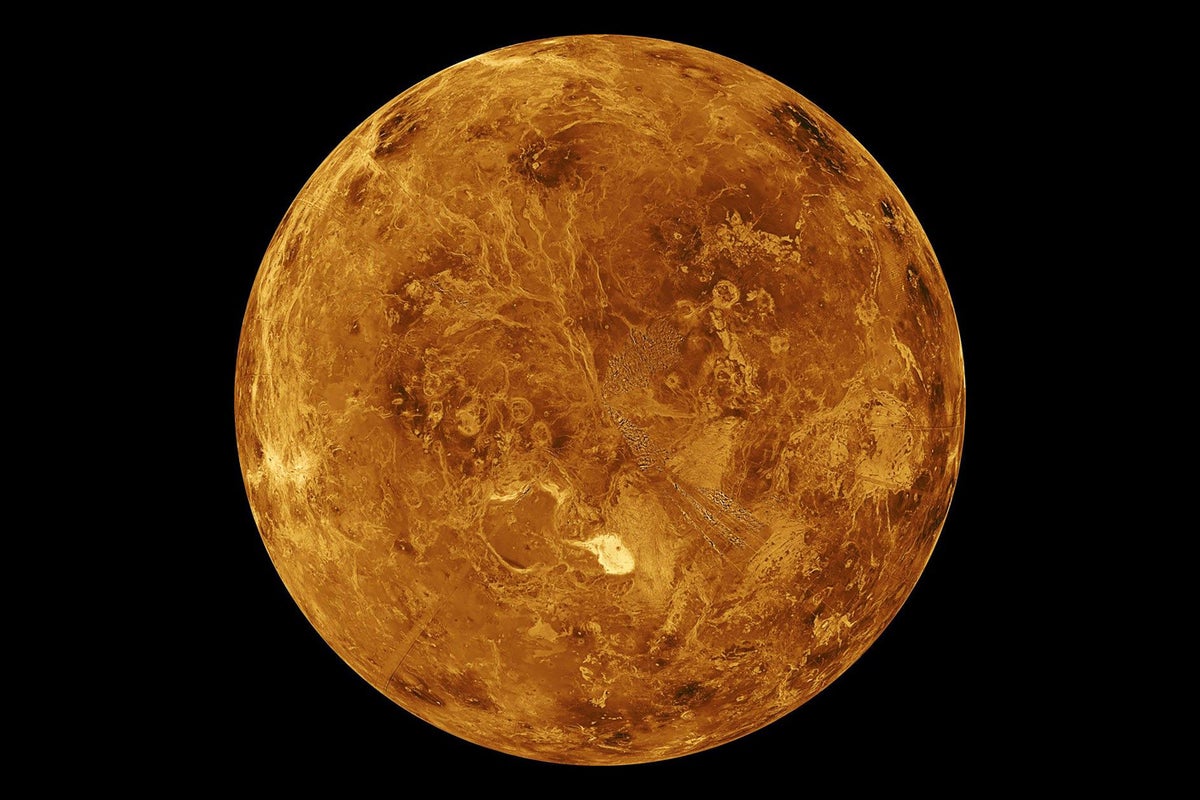

The northern hemisphere of Venus, as captured in the radar data of the NASA Magellan spacecraft. Some of the circular characteristics that are seen in this image are the crowns, mysterious formations that suggest recent studies could be sites of geological activity in progress.

Earth’s geology is frankly vital. Here, the giant “plates” or the bark of the bark separate and break as pieces of an ever changing planetary puzzle. The mountains rise, the volcanoes throw and the earth the earthquakes while the cortex is constantly remake in the incessant cycle of the plaque tectonics. This is a process that controls carbon flow through our planet and stabilizes its climate; If it weren’t for plaque tectonics, the earth may not be habitable at all.

No other rocky world in our solar system has something that approaches the degree of geological activity of the Earth. At least, that is what scientists used to think. Mercury, Mars and the moon seem essentially inert. But Venus, our closest neighbor and the only other great rock world around the sun, is now beginning to seem much more lively than I thought. A new look at the data of the Magellan probe of NASA has found evidence of active doses of tectonics of circular volcanic characteristics called Coronae-on Venus Today. The finding, published on Wednesday Scientific advances, It provides some of the best tests to date that Venus is not dead, at least, not when it comes to tectonics.

“Venus works differently from the earth, but not as different as what was originally assumed,” says the co -owner of the study, Anna Gülcher of the University of Bern in Switzerland. “We should think about tectonics not only as a black and white image.”

About support for scientific journalism

If you are enjoying this article, consider support our journalism awarded with Subscription. When buying a subscription, it is helping to guarantee the future of shocking stories about the discoveries and ideas that shape our world today.

“As fundamental questions as” Venus is alive today? “They are extremely difficult to respond,” says planetary scientist Paul Byrne at the University of Washington in St. Louis, who was not involved in the study. This new evidence of geological activity around the crowns suggests “the heart of Venus still beats today. I think it is extremely invaluable so that we understand the great rocky world next door.”

Venus is called “evil twin of the earth” for a good reason: the planet is almost exactly as great as the earth and is made of approximately the same things. But although the earth is a world of vertical water, Venus is an infernal chamuscado landscape with temperatures hot enough to melt lead, a sky and an air of sad and permanently cloudy air that crushes the spacecraft as if they were cans.

For a while, it was widely supposed that Venus was as dead inside as outside. Lacking any obvious plaque tectonics, which can help release the internal heat interior in the world of the world, it was thought that it simply boiled as the content of a pot in a stove in a stove. According to a popular hypothesis, the pot was possible to get wounded: after frustrated heating eons, about 800 million years ago, the exterior housing of the planet was reduced and the entire surface of Venus was paved with bare fresh lava. And, according to thought, with all that heat dissipated, the geology of the planet was basically closed.

But the evidence is increasing that Venus is at least geological, still kicking. In particular, in 2023, two researchers examining Magellan’s data, 30, realized that the probe had captured a volcanic eruption in the act: the radar images of the Maat Mons volcano that were tasks that were shown with months apart. Venus, apparently, still has active volcanoes. Some researchers now think that they could also have active tectonics. And in 2020, Gülcher and his colleagues showed through tectonic simulations of Venusian that the mysterious ring -shaped crowns of the planet could be a good place to look for such activity.

Tectonics refers to the processes that deform the fragile outer layer of a rocky planet. On Earth, this outer cover, the lithosphere, which includes the bark and part of the upper mantle, is divided into tectonic plaques that move on the hot plastic mantle. When two plates collide, one of them can slide under the other and dive into the mantle in a process called subduction. On Earth, the subducts begin to melt as they sink, feeding volcanoes along the limits of the plates. These volcanoes include Mount Fuji in Japan and the Cascade range of western North America.

Unlike Earth, Venus does not have global plaque tectonics. The new study suggests, however, that around the crowns, something quite similar to the subduction could be happening.

Gülcher and his colleagues simulated several tectonic processes that could be occurring around the crowns and compared their predictions with real observations collected by Magellan’s investigation 30 years ago. The comparisons were more than to the skin: the researchers used gravity data to take a look at the underground. The hot rock is generally less dense than the cold rock, and the variations of thesis density of the place can correspond correspondingly the resistance of the gravitational field of a planet. Then, Magellan’s space mapping of Venus’s gravity can “see” if there is hot and light material under a crown, a sign that the rock actively rises from the mantle below.

Of the 75 crowns that the team could solve in the gravitational maps of Magellan, 52 seem to be geologically active. The predictions and real data were aligned so well for some crowns that “we could hardly believe that ours,” says the other co-leader of the Gael Cascioli study or the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and NASA’s County and the County of the University of Maryland. Most of the active crowns were surrounded by trenches, a clue that the old bark immerses itself in the Venus mantle around the thesis Rocky Rings, where it is driven down as the buoyant rock rises from below in the middle of the structure of the ring of each crown. “Basically, if something goes down, something goes up,” says Gülcher. Where the lithosphere is softer and more flexible, the pieces could break and “drip” towards the mantle in the balloons. In places where the lithosphere is more rigid, the entire slabs or the cortex could subduct in a small -scale circular mirror of the land subduction zones, such as those that form the famous volcanic fire ring of the Pacific Ocean.

Working with 30 -year data comes with an obvious limitation: the quality of the data is often not very good compared to the Duta observations. The new study researchers did well with what they had, says Byrne. But the next mission of Veritas (Venus emissity, radio Science, Insar, Topography and Spectroscopy) could work much better, and the team predicted exactly how much better in the document. “The improvement would be extraordinary,” says Cascioli. Instead of limiting 75 crowns, Veritas’ seriousness data set should allow scientists to examine hundreds of the strange ring -shaped characteristics.

For the planned future, Venus is the only other big and rocky world that we or our robotic emissaries will arrive. Understanding why Earth and Venus ended up so different despite having so many help in common, helped us understand the planet itself, and if the rocky worlds are beginning to glimpse other stars are like the earth or the test.

“Venus is the world we probably understand,” says Byrne. “However, it is the only one, it could be said that it is the most important.”