In the early 2000s, when Dr. Alexandra Cvijanovich was completing her medical training in Utah, her team cared for a 13-year-old boy with subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, a degenerative neurological disease that can be fatal. It’s a rare complication of the measles virus that appears years after the initial infection.

The boy had been infected with measles when he was 7 months old, after contact with an unvaccinated child. Years later, he died of the complications, and Cvijanovich has never forgotten about him.

“He … got the virus before he could be immunized. And that’s just a tragic, horrible, preventable death,” she said.

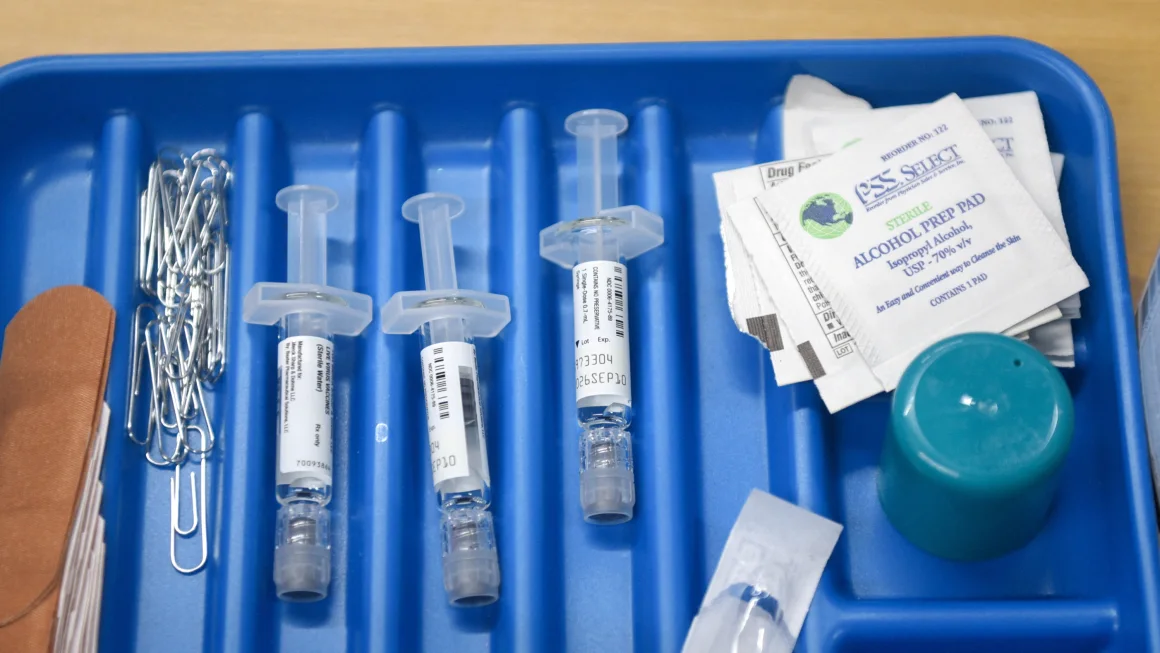

Officials recommend that children get their first dose of the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine between 12 and 15 months of age. Two doses of the vaccine are 97% effective against the measles virus.

To achieve herd immunity, where enough people are vaccinated that infection doesn’t widely spread in the community, 95% of the population needs to be vaccinated, according to the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Now a pediatrician in Albuquerque, New Mexico, Cvijanovich treats people from all over the state – including the southeastern region, which is currently part of one of the largest measles outbreaks in decades, affecting more than 300 people across three states.

She often tells the story of her 13-year-old patient to families that are hesitant to vaccinate their children.

“I tried to use stories of patients that I’ve taken care of,” she said, “and then I also tried to plead with people that they actually think about the greater good of the community around them.”

Many pediatricians say they are seeing an increase in parents who are hesitant to vaccinate their children with the MMR vaccine and others. Here are some of their tips for communicating with vaccine-hesitant parents.

Do: Address specific concerns

Experts say the key to communicating with families about vaccination is to address their specific concerns.

“Tailoring your approach and your communication to that family-specific concern has been the most effective for me and my practice,” said Dr. Edith Bracho-Sanchez, a primary care pediatrician at Columbia University Irving Medical Center. “That is really what helps families feel confident about their choice.”

For some families, this includes addressing worries about side effects they may hear through anecdotes in their communities. Pediatricians say these often circulate in community or family WhatsApp groups or through parent Facebook groups.

“So I am taking time to say, ‘pull it up, let’s look it up together. Who did it come from? Do you know this person? Do you know their full medical history?’ ” Bracho-Sanchez said. “And I do spend time outlining the difference between something happening to someone around the time that they had a vaccine and someone having something happen as a result of the vaccine.”

Experts warn against getting medical advice or information from community social media and urge patients to have conversations with their providers instead.

Other families may have concerns about specific ingredients in vaccines, and doctors recommend understanding which ones are causing worries, like metals or preservatives. Explaining how those same ingredients might also be found in foods or other daily life exposures can quell those fears, according to Dr. Christina Johns, a pediatric emergency physician at PM Pediatrics in Annapolis, Maryland.

Don’t: Let patients forget about the severity of illness

As Cvijanovich has found with her own experiences, helping patients understand the illnesses they are preventing with vaccination can be helpful.

“Vaccines have been victims of their own success,” Johns said. “We don’t see many of these vaccine-preventable illnesses anymore [and] people think they’re no big deal. And the fact is that they really are a very big deal.”

With measles, the consequences can be severe. One in five unvaccinated people with measles will be hospitalized, 1 in 20 children with measles will develop pneumonia, and 1 in 1,000 children with measles will develop encephalitis, or swelling of the brain.

One to three in 1,000 children who have measles will die from complications, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A school-age child who was not vaccinated is among the two deaths that have already been associated with the ongoing measles outbreak.

“Being a pediatrician, watching my patients grow up, that’s the best part of my job,” Cvijanovich said. “I mean, that’s why I go into work every day. I love seeing babies who then enter middle school and graduate from high school and go off to college. That’s fantastic. And the best tool I have to accomplish this is vaccines.”