It’s part of a research effort called Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network, or DIAN. The study participants like to go by a different name, though.

“We like to call ourselves the X-Men because we are mutants, trying to save the world from Alzheimer’s disease,” said Marty Reiswig of Denver, who has been participating in the trial since 2010.

The new study, published Wednesday in the journal Lancet Neurology, found that the risk of symptoms was cut in half for a small subset of 22 patients who had not shown any problems with memory or thinking and had been taking an amyloid-lowering drug called gantenerumab for an average of eight years. The results achieved statistical significance in one part of the analysis but not in others, perplexing outside experts, who struggled to make sense of the complex findings.

“While this study does not conclusively prove that Alzheimer’s disease onset can be delayed and uses a drug that will not likely be available, the results are scientifically promising,” said Dr. Tara Spires-Jones, director of the Centre for Discovery Brain Sciences at the University of Edinburgh, in a statement to the media. She was not involved in the research.

The study authors believe that if people are started on therapy early enough and stay on it for enough time, it could forestall the development of the disease — perhaps for years.

It’s “the first data to suggest that there’s a possibility of a significant delay in the onset of progression to symptoms,” said study author Dr. Eric McDade, a professor of neurology at Washington University in St. Louis.

McDade said this study has the longest-running data for any patients who started amyloid-lowering biologics while they were still free of symptoms.

“We think that there’s a delay in the initial onset, maybe by years, and then within those individuals that have some mild symptoms, even the rate of progression was cut by about half,” he said.

The achievement of this long-hoped-for result comes with optimism but also panic, however.

The research team says the meetings to review their National Institutes of Health grant funding have been canceled twice. Their grant has to be reviewed before they can be referred to what’s known as a council meeting, where funding decisions are made. If their grant misses a council meeting in May, the money for the study, which has been going since 2008, could run out.

“It ends up becoming a really difficult position we’re in and that the participants are in,” McDade said.

Patients could lose access to the study drugs, especially if they’re in countries where the medications haven’t been approved. If people can’t stay on the drugs, researchers may never find out how durable the benefit may be or be able to answer critical questions like for whom the medications work best.

Keeping that group that has been on the amyloid drugs the longest is “absolutely critical,” McDade said.

Long-running studies begin to bear fruit

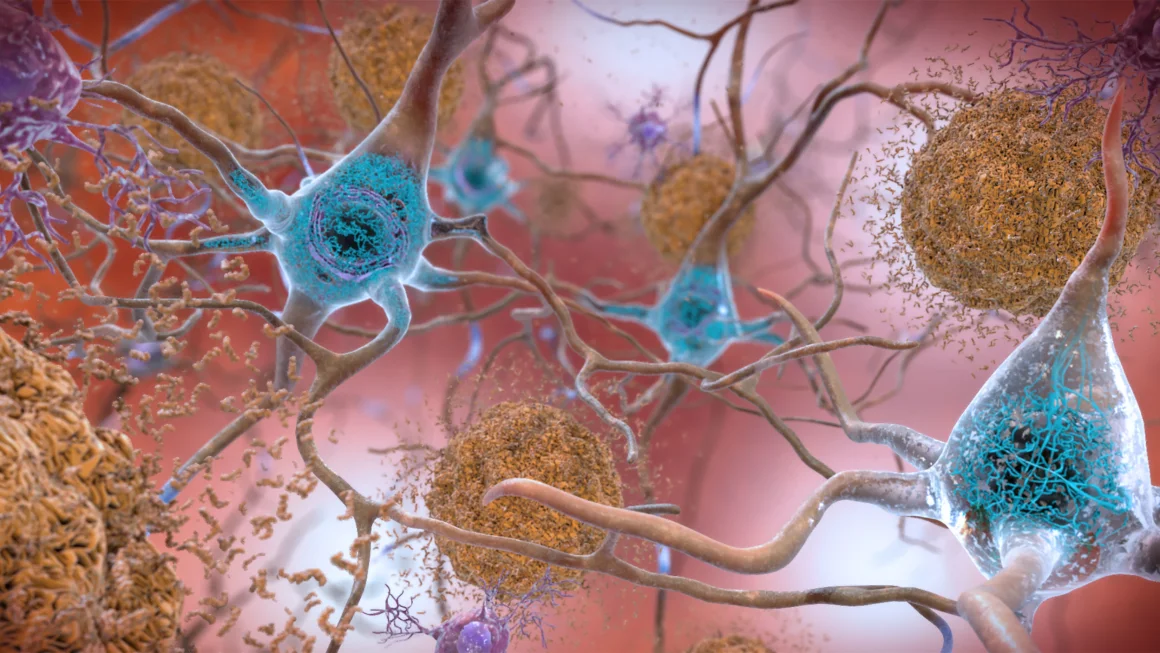

In the 1980s, researchers studying the autopsied brains of people with Alzheimer’s discovered that they were clogged with sticky plaques made from beta amyloid proteins and toxic tangles made of a protein called tau. They theorized that removing these proteins from the brain might delay or even reverse the disease, and they began to hunt for therapies that could do that.

For decades, scientists have been testing a range of biologic medications that recognize and remove beta amyloid proteins, with mostly lackluster results.

In late-stage clinical trials involving more than 1,800 people with early Alzheimer’s disease, one of these drugs, gantenerumab, slowed the progression of symptoms compared with a placebo, but it wasn’t a big enough benefit to pass a test of statistical significance, meaning the result could have been due to chance alone. It was considered a failed drug.